'Don't mourn the passing of the golden age of sportswriting, just be thankful it happened'

GUEST POST: In 1988, Paul Lewis' Olympics coverage won him the highest honour in NZ journalism - 28 years later the papers didn't send any reporters to the Games.

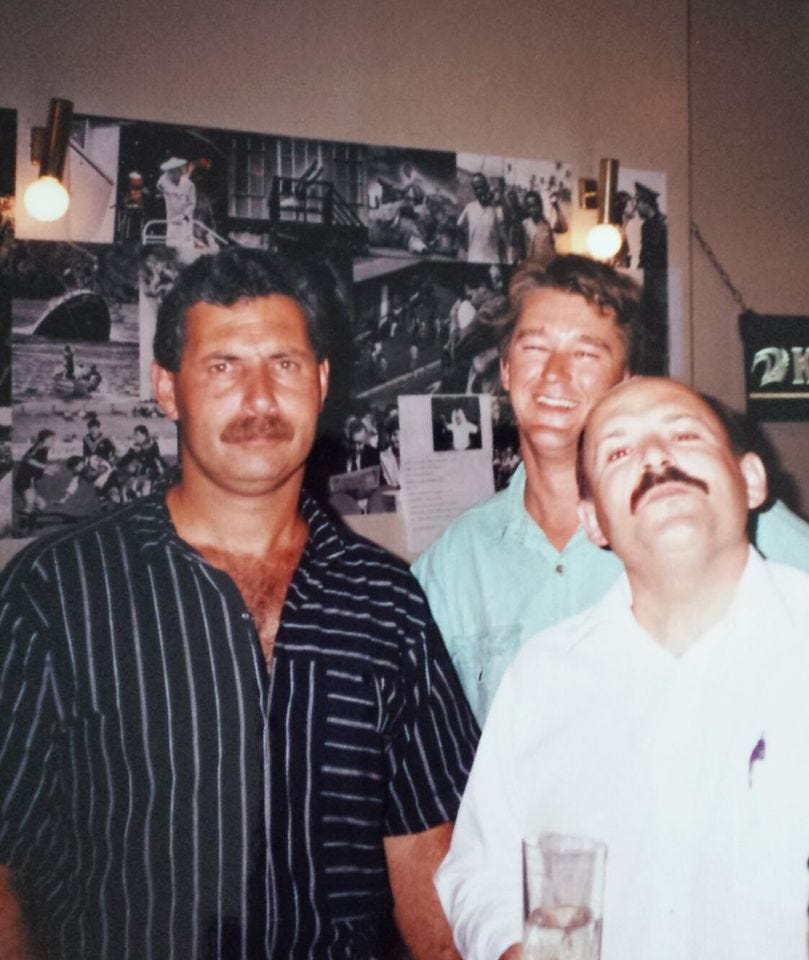

I met Paul Lewis in 2004 when, after months of anxiety-inducing flip-flopping, I made the call to join the sports department of the start-up Herald on Sunday. Those first few months were exhilarating and worrying all at once as the newspaper fought antipathy from within the New Zealand Herald building as much as it did from the existing Sundays, the Fairfax-owned Star-Times and the News.

While the HoS as a whole struggled to find its footing, the sports section didn’t. It was a gargantuan 36-page liftout, a weekly miracle, that owed everything to the sports editor’s force of personality and his ability to cajole and mould stories and copy from disparate talents such as myself, James McOnie, Gregor Paul and Michael Brown. The Tuesday morning editorial meetings could be a humbling exercise as Paul had the sort of body language that left one in no doubt as to whether he thought your ideas were good, indifferent or of the don’t-waste-my-time variety.

Paul was renowned as a very fine writer, having joined the Herald in 1971 as a C1 cadet, the lowliest of the lows, and in the course of a couple of stints had worked himself up to lead rugby writer and Olympic correspondent when he left for Singapore and the PR world in 1991. As sports editor he was the first person I worked for that cared as much about how you told the story as what the story was. Quotes that ran too long or didn’t add to the story, muddled syntax and lazy outros (the final sentence, or pay-off line), would be met with deep sighs.

His brief for this essay was simple: through the lens of his own sports journalism career, outline the ways in which the industry has changed. Paul, of course, has turned it into something much more compelling and lyrical than that.

- Dylan Cleaver

IF THERE was a single moment when I realised I was lucky enough to be part of a golden age of sportswriting, it was in 1984, in the Los Angeles sunshine, in a square in the Olympic athletes’ village.

I was searching for New Zealand middle-distance track athlete turned marathon specialist Rod Dixon. Not here, I was told, staying outside the village with a friend.

That happened to be Burt Bacharach, composer of countless hit songs. They were mates; Dixon chose to stay in the Bacharach mansion rather than the hurly-burly of the village. I had a story. I rang Dixon. Turned out, Bacharach had even set him up for a kind of a date (though not really) with neighbour Barbra Streisand.

So I tapped out a piece on my laptop – one of the first of its kind, a dense brick requiring a durable lap; a Model A Ford to today’s Teslas. Things like the internet and email, the common use of, were still years away. My employers, the New Zealand Herald – for whom I still work today (a third tour of duty) – equipped me with a weird device called an acoustic coupler for pinging copy down a phone.

It was the pre-dawn of the digital age; the coupler produced an incomprehensible electronic soup of words and digital impulses that somehow re-assembled itself into a story at the other end.

The irony is inescapable. I was the first person in Herald history to file by laptop. Had I known what damage the digital age was about to inflict on sports writing, I might not have been so impressed – either with the technology or myself.

Fast forward more than 30 years, and sports desks in newsrooms around the world are faint outlines of their old selves – often under-manned, underrated and under siege. They are collateral damage from the internet age, along with bank branches, CDs, cameras and bookshops.

In New Zealand, over the years, sports desks in the Herald and Stuff newsrooms shrank as the effect of the digital age – free access to news; less revenue from digital ads – bit. The two major media groups also ended their association with a number of regional sportswriters.

Sportswriters and sub-editors were shelled in Australia. In the UK, the Daily Telegraph decided to lose many of its football writers, replacing them with in-office sub-editors writing the games off TV. In London, a friend on the Daily Mail was asked to help make journalists redundant. His task completed, his last act unfolded in a small room when, as thanks, he was himself made redundant.

In 2016, after a battle with rights holders, both the Herald and Stuff decided not to send anyone to cover the Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro. This year, the same decision – for different reasons – was taken re the Tokyo Olympics.

The outcome was a dagger in the heart for anyone advocating quality sports writing. The number of readers soared and spiked, even though coverage was taken from the world’s news agencies, supplemented by phone calls from the office. It produced little not already seen on TV. Yet the numbers performed as if it was gold-standard, world-class fare.

To fully understand what’s being missed, let’s go back to that sunlit square in the athletes’ village in 1984. I was in Los Angeles on my own. My brief – an enlightened one for the time – was simple: one story a day. Don’t hare around all the Olympic venues trying to cover everything when news agencies were doing that; fix on one story a day and do it better than anyone else. In old school parlance, a “writing job” (as opposed to reporting).

That one story filled the back page of the Herald (in those days still a broadsheet) daily with a large picture from ace Herald photographers Paul Estcourt and Ross Land, the latter paying his own way. We looked for news, colour, profiles, features – sport-based, mostly, but anything different, giving readers a strong sense of the Olympics, the host city, our team and a Kiwi perspective.

At the Seoul Olympics of 1988, I heard about student riots, battles with police near the Olympic village. We found our way to a university, stumbling on a room where students were filling petrol bombs for that day’s protest, many dangerously smoking as they worked. “The bomb room” and our Olympic coverage won us New Zealand’s highest journalism award that year.

At the Beijing Olympics of 2008, the remarkable Usain Bolt’s double world records were the story of the Games. By then, New Zealand’s teams had grown. The 130-strong team of 1984 was 199 by the Rio Olympics; 212 by Tokyo. A team of that size means a team of journalists are required to cover it. Only none did.

Most sportswriters get into the business because of a passion for sport. Rugby, the Olympics and cricket were what drove me. A young man then, I was an Auckland club rugby player; Saturdays were needed off – the big working day for any sports journalist.

So I worked in news, only leaping the fence after several years in the newsroom, including stints as a crime reporter, two years in the parliamentary press gallery in Wellington, and as a “fireman” – someone not attached to any particular beat but available to handle pretty much any assignment.

My first, bylined, front page news lead was my eyewitness account of a “towering inferno”, a tall CBD building which went up in flames at night, occupants rushing to safety. After I filed the story on deadline, the news editor’s lightning analysis drew laughter from the sub-editors’ desk: “Lewis! People evacuating themselves does not mean what you think it does.” Ego is often a casualty in newsrooms.

I mention this because I fear precious few people will make that kind of journalistic journey from news to sport now. So it’s important at this point to underline some key disclaimers. I do not want this piece to be misunderstood as the recriminations of an old hack convinced everything was better in his day. Nor do I seek to point the bone at my current employer and others – forced to take measures more to do with survival than profits.

NZME/the Herald have been caring employers, particularly the current regime, even if they’ve had to make hard decisions. When cancer prevented me from covering the 2012 London Olympics, the company told me to take all the time I needed to recover – highly supportive stuff which only increased my loyalty. Nor do I mean to denigrate the efforts of today’s sports writers; there are many fine operators doing excellent work I read every day.

But sports desks and sportswriters around the globe have been hard hit. My third time at the Herald began in 2004 as foundation sports editor of the Herald on Sunday – almost certainly the last major metropolitan print newspaper launched anywhere in the world. In those early days, we produced a full-colour, 36-page sports insert every week – full of good writing and interest.

I moved into my current role – on the commercial side of the business, involved with a new revenue stream – in 2014, partly because I could see the clouds over sports writing changing from cirrus to cumulonimbus; partly because the new job involved skills I had but weren’t being used.

Sports desks are cost centres, not revenue earners. They help bring the eyeballs and reader engagement that is the life blood of the digital age, but sports pages attract few ads and, when the eye of management seeks areas to employ the knife, the sports desk is all too visible.

Many senior people have been made redundant but are relied on as freelancers, more economic than the same person being a staff member. Radio Sport, the full-time sports station, closed last year unable, as the bean-counters have it, to “wash its face”. The TP McLean sports journalism awards, named after New Zealand’s most famed sports writer, have gone into abeyance, mostly because of the pandemic but also because the potential number of entrants has shrunk.

Sports bodies have recognised this digital sea change; they have geared up on social media or through their own websites to cut out the middle man – increasingly addressing fans directly, lessening reliance on mainstream media.

With numbers down on sports desks everywhere, there is more work, less time and less opportunity for those remaining to do the basic contact work essential for any journalist wishing to keep a finger on the pulse of the beat they are covering. Staffs also tend to be younger and less experienced – they cost less as they service the ever-hungry digital story flow on websites.

“Feeding the beast” was how TP McLean used to put it. However, he was only referring to the daily grind of writing on a Tuesday, for example, for a newspaper published on Wednesday, not the constant pressure for fresh fodder for a ravenous receptacle.

The Herald has made some enormous strides, investing in investigative and data journalism and other strong facets of daily journalism to bolster “Premium” content and boost digital subscriptions. But few media organisations have made many investments in sport and, while the emphasis is still on news breaks – “scoops” – the ability to do so is compromised, as is the opportunity to attend global highlights like the Olympics, providing bespoke perspectives and insights.

Producing great readership numbers without sending anyone to the Olympics is wonderful for the media organisation concerned, but dims the appeal of sports journalism as a career – and of readers seeing much more than the daily thrash and updates, much of which is similar no matter where you look. Big reads, good writing, colour and entertainment are not gone, but comparatively rare.

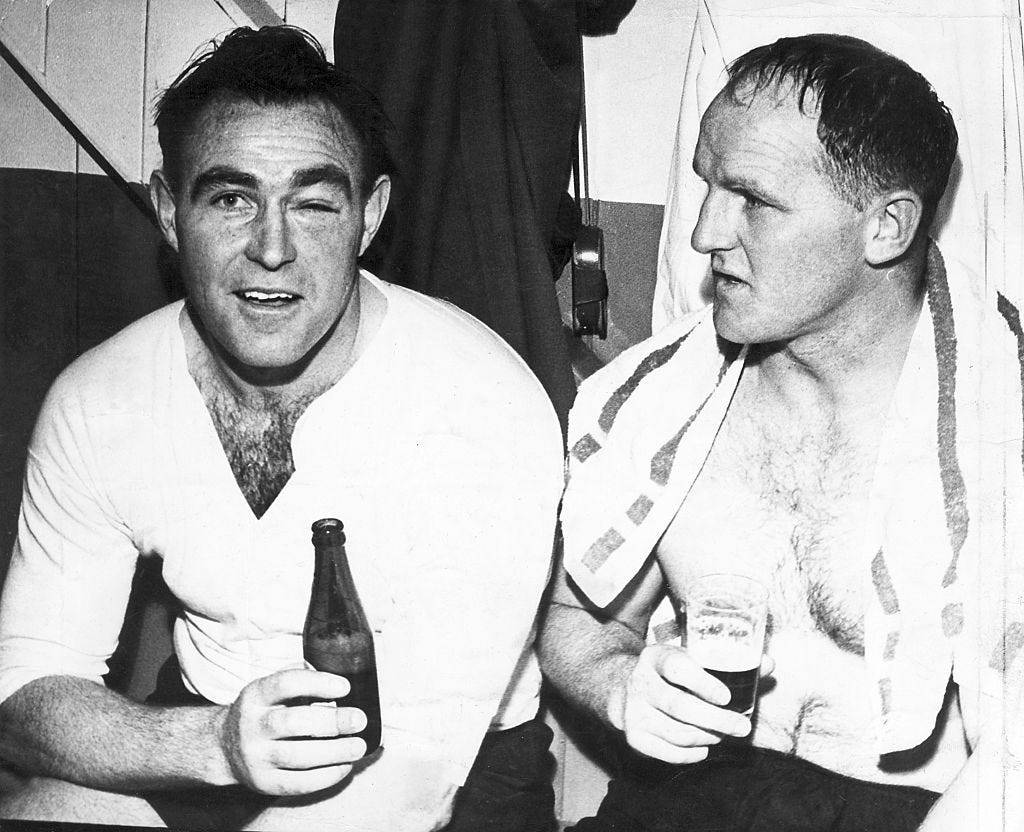

It’s a scenario that McLean and Don Cameron – two premier Herald sports writers for decades – would not understand. McLean was a rarity, a sportswriter who actively and directly increased circulation figures with his writing.

He was required reading, not just because his was an era with little competition other than newspapers. He was a crusader, a deep thinker interested in the effects of intense pressure on athletes. He had a network of contacts and always knew what was going on. He had deep knowledge of the sports he covered, plus beliefs (like attacking rugby) that fuelled an often caustic pen.

One of New Zealand’s revered All Black captains, Wilson Whineray, told me reading McLean was not about entertainment – but being informed. His father, even though he had an All Black son, read TP closely: “You watched the game… then you bought the Herald on Monday and you read McLean to find out what really happened. My father did that – and so did many other New Zealanders.”

Sure, a different time with different context – but sports writing was a considerable enterprise then and in succeeding years. You’d hesitate to call it an art form but, at its global best, it came close at times and was (and still is) so much more than updates and word assemblage.

In McLean’s day – and my own when writing All Blacks rugby for several years – the media corps used to travel with the All Blacks, often on the same planes, staying in the same hotels. It built trust and familiarity; it allowed insightful news, profiles and feature pieces to be compiled.

I was moving along the corridor of the All Blacks’ hotel on tour when a voice boomed out of a room’s open door: “Lewis! Get in here.” It was a prominent forward of whom I had written things less than flattering in the immediate past. A bollocking loomed. But he put the kettle on, made us both tea and chatted away like the South Island farmer he was… about everything except what I’d written.

These days, that kind of intimacy and understanding has been replaced by “them and us” attitudes (on both sides). There are fewer opportunities for developing relationships and insights into our sports heroes beyond the vanilla press conferences that pass for media relations these days.

Media spent a lot on such tours – and still do, where the All Blacks are concerned. One of my editors, whom I disturbed gloomily examining the receipts from an expensive All Blacks tour, sighed: “These people were living like kings.”

I often say to contemporaries, many of whom mourn the passing of a golden age, not to be sorry it’s over but to be glad it happened. It’s more difficult to find a similar message for today’s sportswriters.

A Fleet St scribe (this may be urban legend but a friend on the London paper involved swears it’s true) returned from a football trip to the Middle East years ago. When he filed his expenses for reimbursement, he included a claim for a camel he’d bought to aid a feature he’d written: £250. An accountant arrived at his desk. Where, he inquired, was the camel? The newspaper owned it and was keen to know its whereabouts.

Oh, all right, the journalist sighed, snatching back the expenses form. He crossed out the words “Purchase of camel”, replacing them with “Funeral expenses for camel”.

Maybe it’s good that such things stay in the past. However, as far as sports writing and sports journalism is concerned, it’s harder to see a future where that joke has much relevance.

MIDWEEK BOOK CLUB

What is it? C’mon Red! A celebration of Marist St Pat’s rugby

Who wrote it? Tim Donoghue (with assistance from Paul Donoghue and Brian Dive)

Publisher: Tim Donoghue Publications (2020)

Genre: Club history

Reviewer: Dylan Cleaver

I have always had a soft spot for hyper-specific sports histories and C’mon Red! fits nicely into this category. Even still, I might have been inclined to give this one a miss if it wasn’t for the fact I spent a couple of years in Wellington at the start of the 1980s, attending Ngaio Primary school, even if the latter part of my final year there was spent at nearby Cashmere Ave as Ngaio underwent renovations. Even back then, I was an avid follower of club rugby results and it seemed to me that the Jubilee Cup was always a two-horse race between Petone and Marist St Pat’s.

The other thing that caught my eye was the fact Marist St Pat’s was a relatively new entity, formed out of a merger between Marist Brothers Old Boys and St Pat’s Old Boys - two branches of the Catholic tree (some might even say “Mafia”) joining to form a sturdy trunk.

Donoghue’s book is lovingly curated and that is no surprise given his father, Paul, captain of the Second New Zealand Expeditionary Force team in the Western Desert during WWII, wrote the 50th anniversary of Marist Brothers Old Boys way back in 1969, two years before the creation of Marist St Pat’s.

The book faithfully details the club’s successes, its key players (and occasionally the ones that got away, like Dane Coles) and faithful servants, but it is also rich in colour.

Such as the time the 2008 Jubilee Cup-winning side took the trophy on the end-of-season trip to Lake Taupo. The cup found itself on the bottom of the lake under 40-feet of water after an ill-advised and presumably drink-fuelled leap off a fishing boat by a nameless player. A dive team recovered the trophy the following day to the relief of the panicking and hungover players.

The author himself says his favourite chapter was the one on Stanislaw Witkowski, who arrived in Wellington aged 10 in 1944, “on the run” from Hitler and Stalin. Donoghue outlines his journey from Poland to Siberia, then out of Siberia to Kazahkstan, Iran and eventually on a ship to New Zealand, where he fell in love with rugby and Marist.

If you have a connection to the club or just want a little slice of club rugby history, email donoghue.tim@gmail.com.